By WILLIAM SHANNON

We drove southeast from New Orleans, out on Route 23 following the Mississippi River toward its mouth. Solid land on either side became scarcer and scarcer and the towns of Port Sulphur, Empire and Buras-Triumph and other rural settlements were primarily made up of mobile homes, sportsmens’ cabins and simple houses on stilts—dwellings that could be moved quickly or abandoned with a noble toast when the time comes.

When my girlfriend, Rena, and I saw a sign for Fort Jackson, I recognized it from a reference in one of the letters a great-great grandfather of mine wrote home during the American Civil War. Along with the 128th Infantry Regiment, Isaac J. Mickle and hundreds of other young men from the Hudson Valley spent much of their war-time experience in Louisiana.

“We are encamped two miles below New Orleans in the old battleground where Andrew Jackson fought in 1812,” Mickle wrote in January 1863 from Camp Chalmette. “Lately occupied by the rebels… When our folks took Fort Jackson the rebels thought it was about time to leave. They spiked all the cannons and then left.”

We pulled into Fort Jackson, which was built to protect New Orleans seventy miles upriver, after the war of 1812.

We parked and wandered through grassy areas between old fortifications trying to imagine them alive with cannon fire.

Back on the road, we slowed as we approached the little fishing town of Venice. Most of Venice is built on one long wooden platform, elevated twenty feet high with stairs leading down to docks on the water.

Venice is the last town toward sea in this area on the map, but we kept on Route 23 for good measure until a mile or two later when stopped by a flooded roadway. We parked and sat on rocks near the road looking over the water and finished a bottle of champagne we’d opened at Fort Jackson to celebrate Rena’s birthday.

On the way back, around 3 p.m., desperate for coffee, I convinced myself that a roadside ice cream stand must have some, but the young woman seemed to think I was strange when I asked if they had any.

Thirty minutes or more later, we pulled into a gas station. I asked for coffee in the deli side of the building and the lady started a fresh pot. Men in work clothes sat at a deli table, legs stretched out, laughing and drinking as the warm afternoon faded away. A dozen or more empty beer bottles stood on the table.

“Hey—your wife’s waitin’ on you, man,” one of the men said in a thick bayou accent, smiling and nodding toward the other room after I came out of the bathroom. I thanked him and didn’t correct him.

The next morning in New Orleans, we ate bacon and eggs and rice outside the little cottage we rented through Airbnb. The eight-by-forty one-bedroom cottage was a sweet accommodation. It made us daydream about layouts, what’s needed most and what we could go without. With 320 square feet, you start getting creative with, and appreciative for, almost every square foot.

That day we drove twenty-five miles outside New Orleans along Lake Pontchartrain to get to LaPlace, Louisiana, where we’d booked spots on a pontoon boat for a tour of Manchac Swamp.

On board, Captain Allen eased the boat through the bayou and into a canal in the swamp and heaved marshmallows toward most of the alligators we saw.

In between sharing his knowledge of the bayou and its flora and fauna, the captain set into a few diatribes against formal education.

“One of the worst things ever happened to us was the education system,” he said. “We were actually told in the school system, if we’d spoke one word of French in school we’d have been beaten or thrown out. We been here before the 1700s and our language wasn’t accepted. So a lot of us didn’t go.”

And later on, in his fast-paced deep-bayou voice, Captain Allen said, “Katrina didn’t hit Louisiana—it hit Mississippi. The news media made it look like it came through here. It was almost a hundred miles away from New Orleans. But when the government people blew the levees—which they lied and said they didn’t—. Dynamite don’t just go off by itself. If it had hit the city of New Orleans you wouldn’t be there today ’cause they wouldn’t have rebuilt it, it would’ve been so bad.”

Soon, the captain relayed a story that has lured ghost hunters to the slow waters of the Manchac.

“Town was called Frenier. Frenier’s the name of a tree. And here they grew crops. Grew black-eyed peas. Cabbage. Lettuce.

“In the early 1900s there was nine hundred people living right here. Seven miles north of here was a village called Ruddock. A logging village. Had about nine hundred people living in it. And there was two smaller villages in between.

“But right here in the town of Frenier, was an unusual lady—alligator right there. A little tiny black lady. Her name was Julia Brown. And the reason she was strange was ’cause all her life, over fifty years, she kept telling stories to the people. She even sang songs about it. She was telling the folks that if she ever left this island, she’d take it with her. People thought she was crazy. But it happened.

“One night in 1915, Julia Brown passed away. And the next morning before the sun come up, a storm hit. It wiped out all four villages.

“Right here in Frenier alone, out of nine hundred people only twenty-two survived.”

He slowed the boat and we inched along.

“Julia Brown was peculiar ’cause as a young girl, she believed in Marie Laveau. And as a young girl she got to meet her. That was the problem—when she came back to the swamp and tried convincing these people she knew voodoo, well, they knew for sure right then and there that she was nuts.

“She was talking to the wrong people. ’Cause we don’t believe in voodoo. We know nothing about it. But if you turn the TV on, on the TV shows, voodoo people are always dancing out in the swamps. That’s not real. That’s called TV. Voodoo people don’t come out here; they’re scared to death. They don’t ride in boats, they don’t walk through swamps and they’re highly afraid of spiders—they live in the city. I know that for a fact.

“But after the black storm of 1915, ya’ll, this is all that’s left of the town of Frenier.”

He cut the motor and the boat drifted to a narrow piece of solid land. Behind a grassy boat landing was a crooked iron fence, a green archway painted green and a cluster of white wooden crosses protruding from the ground.

“This is how we bury our people where I’m from—on high ground. This was a high ridge. Everyone was buried on this high ridge. Several hundred bodies. All but one person. Julia Brown.

“Because of what she believed in, they actually wanted these people to rest in peace. So they buried everybody on the hill, but they paddled her body across the bayou and they buried her by herself in a low-lying area. Just so these folks could rest in peace.”

On the ride back, we wondered how many of the story’s details were swamp myth but soon decided that it doesn’t matter.

Feeling like a sagacious traveler, I asked Rena to keep us off interstates and to keep us on roads along the Mississippi River. Our scenic route ended up keeping us geographically close but on the land side of the Mississippi River’s dirt mound levees, out of view of the waterway. It also took us past major energy operations of Chevron, Exon-Mobil, Halliburton and others, and delivered us, after taking three times as long as the interstate, into New Orleans’s congested workday traffic.

We spent almost the entire next day in the French Quarter. We drank hurricanes before lunch and I vowed to drink nothing other than hurricanes, a rum-fruit juice-grenadine concoction that is a New Orleans staple, for the rest of the day. A sugary, happy-go-lucky daytime buzz was the result. I even encouraged Rena to shop in some stores while I drank one the hurricanes along the Mississippi River walk. (Drinking outside is legal in the French Quarter—lots of bars offer drinks-to-go from windows facing the streets.)

A man playing a trumpet in a park finished one tune and a lady asked if she could make a request. He nodded and she said, “When the Saints—” and within second he broke into the song, his head bouncing with the notes.

A young street band two days earlier in the French Quarter played a rendition of the jazz classic, “Sunny Side of the Street.”

Trombone, banjo, fiddle, washboard, stand-up bass. And a plastic bucket in front for tips.

“Grab up your hats, coats, boots, everything

Leave your worries on the doorstep, cause we’re going bye bye

Just direct your feet to all you’ll meet

On the sunny side of the street.

Can't you hear the pitter and the patter

of the rain drops trickling down your fire-escape ladder?

Life could be so fine,

Fine as mm-wine.

I used to walk, walk in the shade with my blues on parade

But—I’m not afraid

It’s over, Casanova,

And if I never had one cent

I'd be rich as Rockefeller

Gold dust at my feet

On the sunny side of the street.”

That night, after eating dinner in front of the flaming fountains of Pat O’Brien’s Pub (shrimp and cheesy grits that were formed into what looked like a large slice of cornbread, fried, all in a soupy mix of Cajun spices), we ducked inside the venue to check out the dueling piano show the bar puts on every night.

Two women playing pianos facing each other and an elderly man tapping a metal tray between them took requests written on napkins from the audience. One of the women asked that all napkin requests also list where you’re from and what you’re celebrating.

During one of the songs, I walked up and put a napkin on the side of the piano of the lady on our side of the room.

They decided neither knew how to play my request—Mexicali Blues by the Grateful Dead—and asked for an alternate request.

I called out El Paso—a Marty Robbins tune that the Grateful Dead also played—as an alternate and the woman on our side was stumped again but looked it up on a laptop and played it a few songs later.

“Kind of a strange song for a one-year anniversary request,” the woman said before playing El Paso. “A song about bar fights and heartbreak.”

We laughed with the crowd and I almost called out that it wasn’t my first choice but then remembered that Mexicali Blues also happens to be a song about bar fights and heartbreak.

Afterward, I got another hurricane from a to-go bar and we walked down Bourbon Street, the French Quarter’s most active drag, where a spirit of Mardi Gras seems to live every night.

Blocked off to traffic, pedestrians packed the street.

Signs every twenty feet or so offered cocktails to go. There were offers of coke and couples’ lap dances. A young woman walked topless out of a bar and onto the street.

Men who were lined up on a second-floor porch threw Mardi Gras beads at any female who walked past. The necklaces were piled on the street. The men hit one woman on the head with two or three necklaces at once. She stopped and looked up. “Are you fuc**ng serious?!”

We walked until the street quieted down, turned back, stopped for a while to watch some live music and walked on.

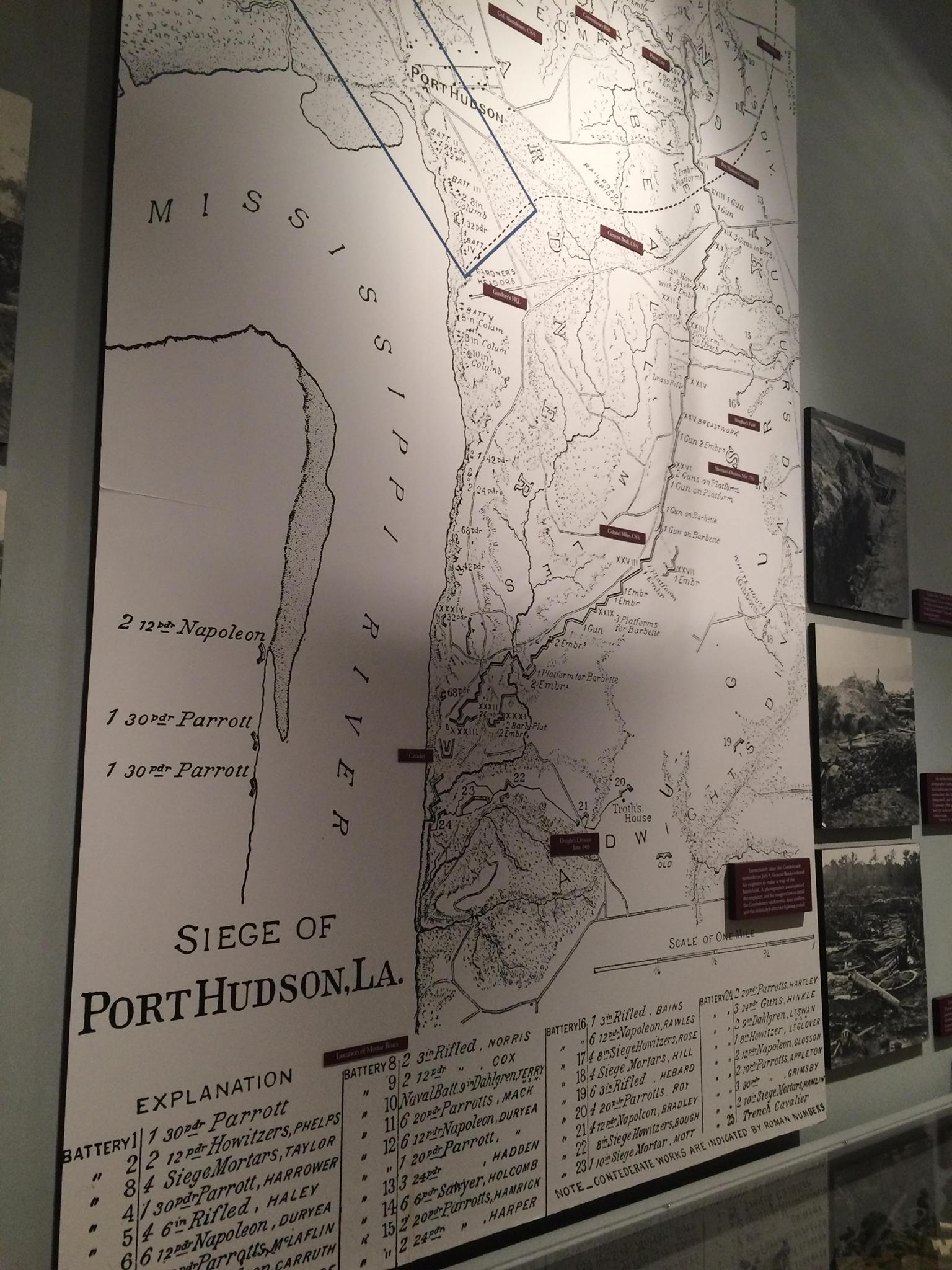

We checked out the next day from the little cottage and drove about a hundred miles north to Jackson, Louisiana, where the siege of Port Hudson during the Civil War took place.

The bloody 48-day siege resulted in Union forces taking control of the last confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River right after Union troops upriver also successfully took control of Vicksburg.

The 128th Regiment from the Hudson Valley played a major role in the siege of Port Hudson. After two major infantry assaults, the Union Army was able to cut off Confederate supplies and after weeks with no incoming food and after hearing of the fall of Vicksburg, the Confederates surrendered. Thousands of men died and thousands more were wounded.

My great-great grandfather was shot through both thighs while fighting with the 128th at Slaughter’s Field during the first infantry assault on Port Hudson on May 27, 1863.

The man in the battlefield museum gave us directions to get to Slaughter’s Field, now a farm on private property, and told us how the Mississippi River silted up in that area and changed course. The river is now almost a mile away, he said, from where it was during the Civil War.

We spent time in the museum and then walked the trails that lead through earthworks and trenches still visible.

After driving down some back roads looking for, and possibly seeing, Slaughter’s Field, we headed east toward Mississippi.

We watched the sun set that evening from a little spit of land in Bay Saint Louis, Mississippi—a town on the Gulf of Mexico that was hit directly by Hurricane Katrina.

We stayed the night in a hotel room above a casino and the next day walked around the beaches of the town. There was a lot of new construction and quite a few empty lots where concrete front steps were all that remained from former houses.

In the afternoon, we allowed time for distractions on the ride back to the airport in New Orleans.

We checked out a NASA visitor’s center and then followed signs for Chalmette National Cemetery and stopped there.

The cemetery, on the outskirts of New Orleans, contains the bodies of about 12,000 Union soldiers from the Civil War, about half of them unknown. During the war, the site was also a camp, according to a sign there. It may very well have been the site of Camp Chalmette, from which 22-year-old Isaac Mickle sent a letter home.

I wondered where the New Orleans hospital might’ve been where he recovered from his wounds after the Siege of Port Hudson.

Past the graves in Chalmette National Cemetery, a bluff overlooks the Mississippi River.

“One of the boys caught a catfish that weighed over 50 pounds on a hook and line baited with pork,” Mickle wrote from a river island dubbed “Quarantine Island” five months before he was shot.

Between the bluff overlooking the river and the thousands of white tombstones, stands an imposing monument with cannon barrels pointing from each corner.

“Dum Tacent Clamant,” reads the base of the monument.

While they are silent, they cry aloud.

***

The title of this column, “Flash,” is short for “Flash of life: a chronicle of efforts to slow life down.” William Shannon runs the website hudsonriverzeitgeist.com. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Globe and The Minneapolis Star-Tribune. His book 'Hudson River Zeitgeist: Interviews from 2015,' is available at the Artisan Shop at Camphill Hudson Solaris at 360 Warren Street in Hudson and through hrzeitgeist.com.

A sign at Fort Jackson.

Bay Saint Louis, Mississippi

Trenches dug during the American Civil War at Port Hudson.

Chalmette National Cemetery in New Orleans.